Life Always Triumphs

Kerry James Marshall, School of Beauty, School of Culture (2012). Photography ©Sean Pathasema/ Kerry James Marshall/Jack Shainman Gallery

“Life always triumphs, and art and spirit are our engines,” Koyo Kouoh, then executive director and chief curator of Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa, told a friend of mine before her untimely passing at only 57 earlier in the year. I’m returning to this quote, shared in correspondence, as I sit down to relive a year in art. The exhibitions I’ve seen in 2025, from London to Europe and beyond, have been questioning, strikingly lyrical, and at times explosively confrontational in their response to our fractious world. Collectively they are proof, to my mind anyway, that the spiritual world of art will always triumph no matter how dark it may seem outside.

From Kerry James Marshall’s powerful body of work that has redefined the possibilities for Black artists working on their own terms, to Peter Doig’s melodic interweaving of memory and place, Wayne McGregor’s embodied enquiries, William Kentridge’s insistence on maintaining “provisional coherence”, and Arthur Jafa’s urgent, political, uncompromising work, what united them all was a refusal to look away. The exhibitions that follow are largely London-based.

Kerry James Marshall’s The Histories at the Royal Academy (until 18 January 2026) is essential viewing. I’ve returned several times, each visit revealing new layers. The American artist is one of the most critical contemporary history painters working today — an artist who has created a safe space for Black artists to make work without explanation, without needing white institutional validation. His monumental paintings, elegantly installed hall after hall at the RA, refuse justification. They simply exist, depicting Black life with all its complexity, dignity, humour, beauty, while claiming an unapologetic presence in the art historical canon. Marshall hasn’t simply made space for Black representation; he has redefined the terms entirely.

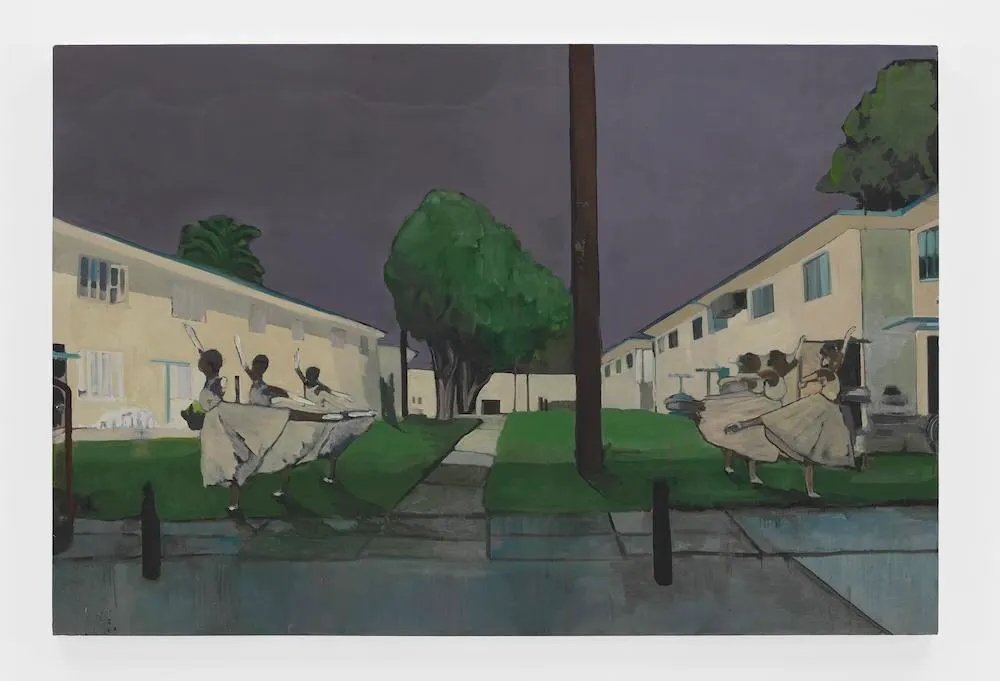

Noah Davis, Pueblo del Rio: Arabesque (2014), Barbican. Photography ©Kerry McFate/Estate of Noah Davis/David Zwirner

More quietly powerful was the retrospective of the late Noah Davis at the Barbican gallery earlier in the year. Gathering over fifty works by the Los Angeles artist who died in 2015 at just 32, the show filled the Barbican’s brutalist walls with Davis’ soft figurative scenes. Informed by found photographs, films, literature and art history, his paintings capture moments of quiet wonder and melancholy with profound empathy.

Central to Davis’ practice was the belief that his role as an artist was to reflect and uplift the people around him, which led him and his wife Karon to found the Underground Museum in 2012: four former storefronts repurposed into a free cultural centre that staged residencies and exhibitions, forging a groundbreaking partnership with MOCA Los Angeles. Davis was one of the most original painters of his generation, whose joyful vision makes his early death all the more devastating — a vision that bridges personal and collective narratives, insisting that painting can illuminate difficult truths while celebrating Black life with unflinching beauty. One evening, live jazz filled the gallery, continuing the conversation Davis always believed art should make possible.

Making music even more central to the show is another fantastic exhibition House of Music at the Serpentine. On until 8 February 2026, British artist Peter Doig has transformed the gallery into a communal gathering space and a living soundscape. “London is full of people obsessed with music and sound,” he said at the exhibition opening. “The idea is to bring these private systems, these private passions, into a public space — to make paintings and sound part of the same conversation.” With his armchairs (shipped across from his home in Trinidad, where he lived for nearly two decades) dotted around the dimly-lit space inviting a moment of stillness, this is far from a conventional exhibition. As Lizzie Carey-Thomas, Serpentine’s director of programmes and chief curator, told me, the idea was to use the gallery’s experimental spirit to push the dialogue a little, see how Doig’s paintings can be presented within another context.

Peter Doig, House of Music (2025), Serpentine. Photography ©Nargess Banks

Doig has always painted with music, and his time in Trinidad deeply influenced his work. At the Serpentine the paintings share the space with restored analogue speakers salvaged from old cinema houses (1950s Klangfilm Euronors and a rare 1920s Western Electric system) playing music from Doig’s vast vinyl and cassette collection daily, with Sunday performances by artists including Brian Eno and Arthur Jafa.

The musical element amplifies what makes Doig’s practice so special: his ability to layer reality with imagination and memory, creating a sense of the poetic that makes his work so absorbing. On a cold, bleak January day I took my mother to the Serpentine. Her sight is frail these days but I caught her transfixed by Doig’s work swaying to the music, her face lit up and her mood full of sunshine for the remainder of the day.

Random International/Wayne McGregor/Chihei Hakateyama, No One is an Island, Somerset House. Photography ©Ravi Deepres

Meanwhile at the Embankment gallery spaces at Somerset House, Wayne McGregor has taken on an entirely different world and medium with Infinite Bodies (until 22 February 2026). The choreographer is presenting three decades of cross-disciplinary work: AISOMA is an AI tool trained on McGregor's archive to generate original movement in live dialogue with dancers; OMNI blends choreography with high-impact visual effects; and a Random International installation sees kinetic light sculptures mimic biological movement. McGregor refuses to treat technology as spectacle or enemy, using it instead to deepen our understanding of movement, memory and ultimately humanness, in the process making the digital feel remarkably physical. It’s a truly fascinating body of work from an artist I’ve long admired.

Elsewhere, London’s smaller galleries have been quietly staging some of the year’s most compelling work. Claudia Alarcón and the Silät collective’s Choreography of the Imagination at Cecilia Brunson Projects presented ancestral weaving as a living, experimental language rather than static craft. This was a beautiful exhibition with artworks hung loosely from the ceiling, swaying gently in the naturally lit Bermondsey gallery. Alarcón collaborates with around 100 Wichí weavers from Argentina’s Gran Chaco region, spanning generations. Here, they respond to Bauhaus émigré Anni Albers’s mid-century encounter with chaguar weaving, creating work without singular authorship, with each piece a collective interpretation passed across time.

Claudia Alarcón & Silät, Choreography of the Imagination (2025), Cecilia Brunson Projects. Photography ©Nargess Banks

At Sadie Coles’ elegant new Savile Row space, South African artist Lisa Brice opened with Keep Your Powder Dry, three bodies of work creating a sequence of defiant tableaux. Responding to the erosion of safety in our present political moment, Brice draws from art history’s depictions of violence — Gentileschi, Caravaggio, Manet, Magritte — and Honour Blackman's 1965 Book of Self Defence. Her women are never passive subjects: they are armed, ready and collectively powerful.

Even more exciting was Arthur Jafa’s GLAS NEGUS SUPREME at Sadie Coles’ original Kingly Street Soho space. This is urgent, political work. The filmmaker and artist has spent four decades documenting Black life, with the show uniting two major moving-image works alongside paintings, silkscreens and cutouts. Jafa’s films layer found and personal footage from the 1980s onwards against sampled scores, creating testimony rather than documentary. Musical icons like Prince appear as ghostly presences across time and geography, the work contending with Black representation, resilience and cultural change.

Arthur Jafa, I just want our love to last (2025), Sadie Coles. Photography ©Arthur Jafa/Sadie Coles

I also enjoyed some of the exhibitions at London’s major institutions, many of which brought canonical figures into fresh dialogue. Tate Modern is marking the centenary of Pablo Picasso’s The Three Dancers by spotlighting the artist’s fascination with theatre — dancers, entertainers, bullfighters. At Tate Britain, Lee Miller’s extraordinary career is examined through surrealism, fashion, war photography and her lesser-known images of the Egyptian landscape in the 1930s (until 15 February 2026). The gallery is also showing J.M.W. Turner and John Constable side by side — Britain's great Romantic rivals, born a year apart (Turner in 1775, Constable in 1776). Critics of the day called it a clash of “fire and water”. Seeing major works together reveals how Turner pushed beyond domestic landscape toward something more turbulent and abstract, while Constable stayed rooted in Suffolk, exploring the same landscapes for their changing light and weather.

I’d like to end 2025 with a personal highlight, particularly as I spoke with an artist I’ve long admired, William Kentridge. The Pull of Gravity at Yorkshire Sculpture Park (until 19 April 2026) offers a fascinating peek into the Johannesburg-based artist’s practice that migrates between so many different mediums and forms of expression. YSP has gathered over 40 works and commissioned new outdoor sculptures, all of which reveal Kentridge’s refusal to give into fixed meaning, embracing instead what the artist calls “provisional coherence”: the idea that understanding is never absolute but emerges through process, only to shift again. As the son of prominent anti-apartheid lawyers, Kentridge is a deeply political artist, always questioning the grand narratives of history and politics by refusing to succumb to fixed truths. His world is about actively inviting multiple ways of seeing through art.

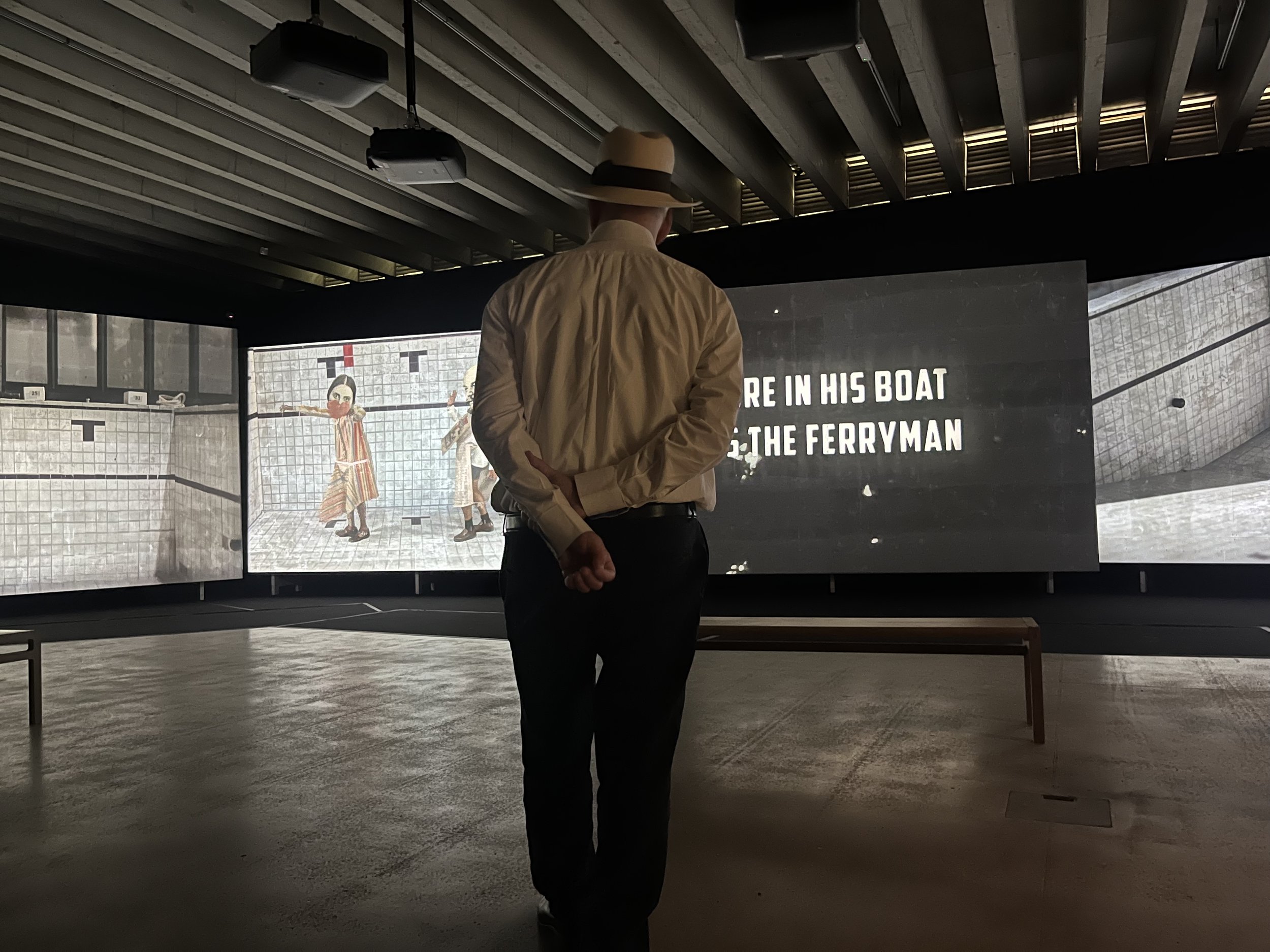

William Kentridge observing Oh To Believe in Another World (2022) at YSP. Photography ©Nargess Banks

Highlights include two video works in one of the gallery spaces: More Sweetly Play the Dance (2015) is a hauntingly moving and strangely beautiful silhouetted procession of figures — a brass band, skeletons, refugees — referencing displacement, disease and endurance. Oh To Believe in Another World (2022) takes an even darker, more politically charged turn, set to Shostakovich’s Symphony No.10 (a work long associated with the composer’s fraught relationship with Stalin) to interrogate the tension between artistic freedom and totalitarian control.

When I asked Kentridge if he had hope in a world that, for many of us, feels increasingly dark and difficult to digest, he told me: “I have both hope and pessimism, both running together. I think to have only one or the other is to blind yourself to part of the world and say, everything can only be a disaster. It blinds you to many things that are happening. And to say everything’s for the best, blinds you to disasters that are very, very present.” And to my mind it’s precisely this refusal of fixed truths that makes Kentridge’s work so urgent for our black-and-white, right-and-wrong, painfully polarising times. Worth the trip north to YSP.

This review was first published in Forbes