From Hero to Parasite

Emeric Lhuisset, Théâtre de Guerre (2012). Photography ©Emeric Lhuisset

Émeric Lhuisset is concerned with photographic truths. The French visual artist examines the complex narrative of the refugee through the medium of photography, articulating a deeper representation than typical photojournalism offers – presenting the human side of the migrant within a wider geopolitical context. Lhuisset is the latest artist to be supported by BMW Art & Culture, the branch of the Munich car firm investing in arts and ideas through its work with institutions such as Art Basel, Frieze, and Paris Photo. His exhibition L'autre Rive (The Other Shore) represents the body of work he created during his BMW Residency at Gobelins L'École de L'Image.

Exhibited initially at Paris Photo 2019, L'autre rive presents Lhuisset's coverage of the century-old conflict in the Middle East. The narrative follows the disappearance of places and people, the humanisation of the refugee against often fixed narratives – in the case of the Kurds, from heroic freedom fighter to anti-hero immigrant. His work depicts elaborately staged sets alongside everyday domestic scenes, selfies, blue skies with dotted clouds that hover over civilisations in conflict, war and disappearance.

I met with Lhuisset in Paris.

Your exhibition is a compelling visual account of the journey of the many refugees, in this case from the battlefields of Kurdistan – in Iran, Iraq, Turkey and Syria – to exile in Europe. This certainly feels like a very personal story. Why the Middle East and the Kurdish plight?

I studied geopolitics and fine art; I then worked in Turkey and Syria for many years as a photographer and artist. I am interested in the reconstruction of Iraq after the war, and so I initially went to Kurdistan because it was safer at the time, and this is how I met the people and discovered their stories.

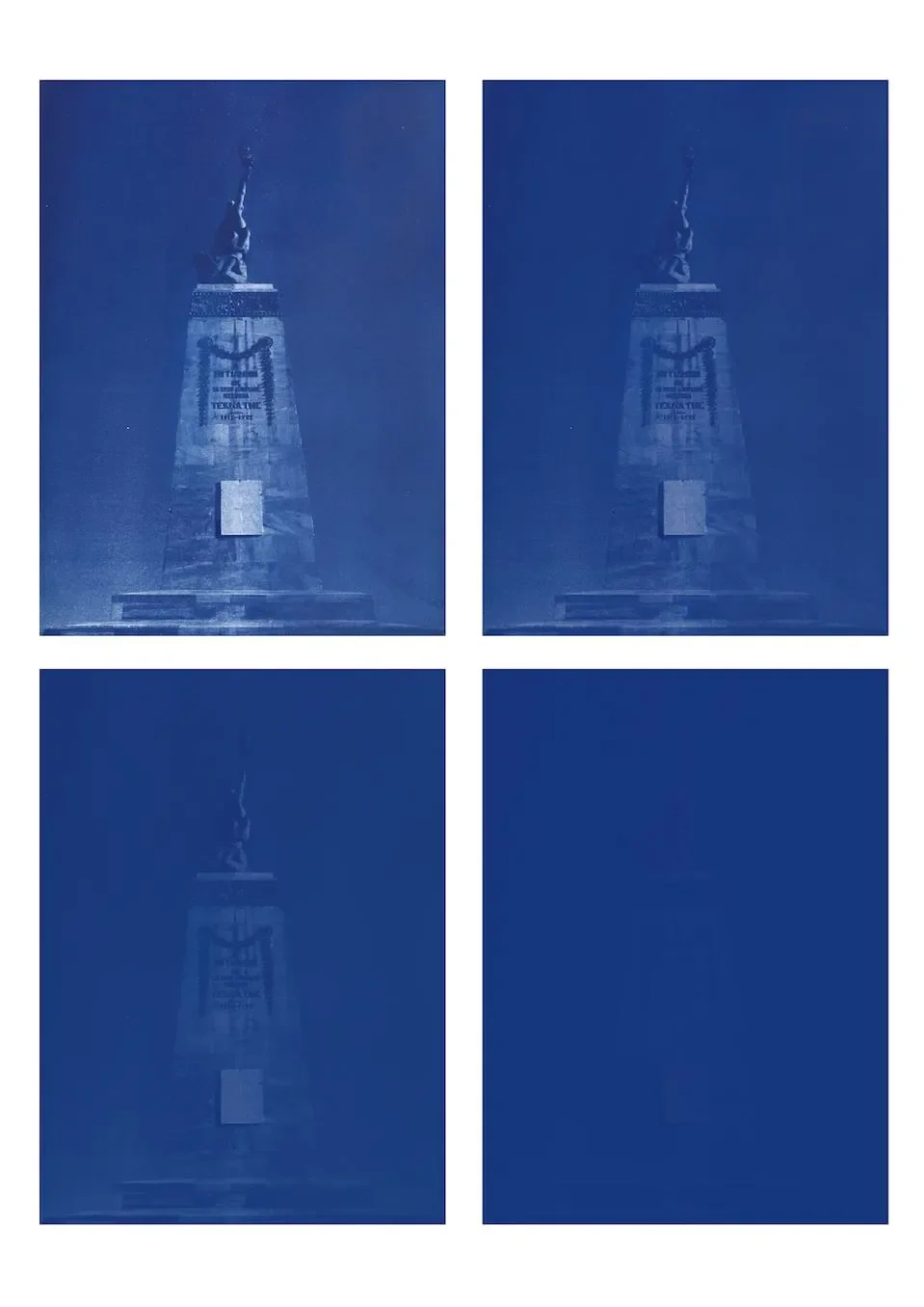

Emeric Lhuisset, L'autre Rive (2019), concludes with a series of fading blue renderings through cyanotype. Photography ©Emeric Lhuisset

What is the central theme here?

What interests me is this idealisation of the freedom fighter in western society. Most governments here have a heroic vision of the Kurdish fighter, but at the same time they mostly see the refugee as a parasite. For this exhibition, I worked with real Kurdish soldiers on the battlefield and later as refugees in Europe. And within the seven years I photographed them, they go from hero to parasite. So how can we change our perception of a person when they cross the sea? I’m interested in the construction of this vision, and I’m trying to deconstruct this vision.

Your Paris Photo exhibition opened with two powerful large-scale images from your series Théâtre de guerre. Your subjects, the Kurdish combatants, are staging dramatic, stylised scenes from classical war paintings. Why create these measured, slow images that contrast with the speed and urgency central to photojournalism?

I took inspiration from the paintings of the Franco-Prussian wars, which influenced the representation of war photography. This was a defeated war, and so showed scenes of the real soldiers fighting not only the victory of the generals. I staged this in Iraq, where I asked the Kurdish guerrilla fighters to act out their battle scenes – replacing their reality within the context of the classical painting.

This must have been tricky to stage given the area is a battlefield. So why take the risk and create these elaborate images?

We are lucky that no one tried to attack us during the photoshoot, with the process taking only 15 minutes before we ran for shelter. These images are central to the exhibition as I am interested in the question of reality, the construction and theatricalisation of war picture. These images look fake, because the movements are adapted from a painting, but they are photographed in a place of war using real fighters. So, the question is: is it true or not?

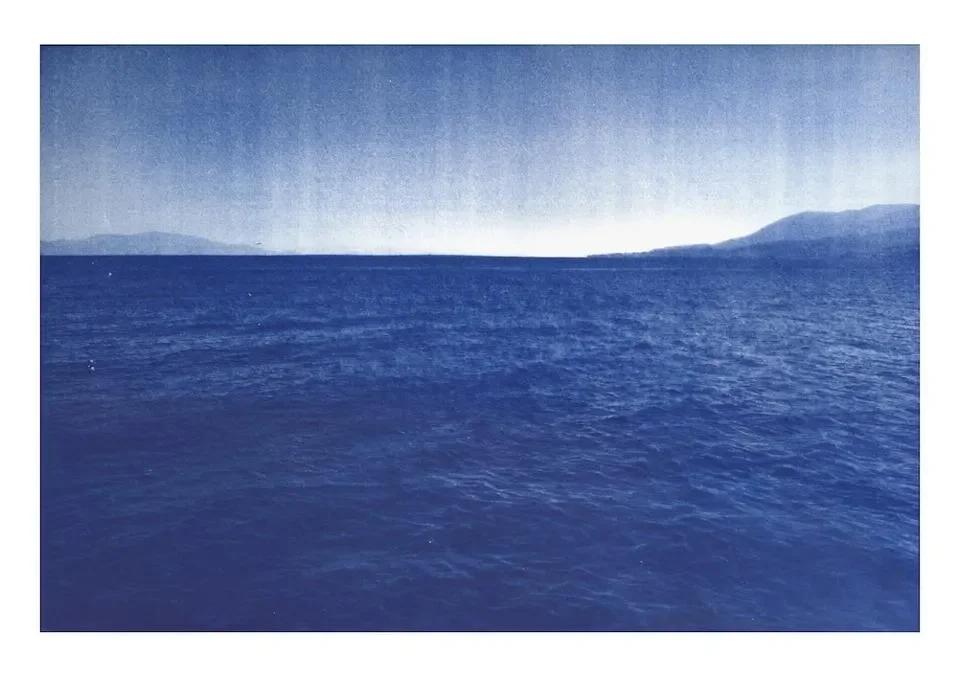

Emeric Lhuisset's L'autre Rive (2019) depicts scenes of the sea where many escaping war and chaos vanish. Photography ©Emeric Lhuisset

In complete contrast, you follow these with simple images of land and sea.

The first shaky handheld video depicts the crossing between Syria and Turkey – the journey taken by those fleeing the war in Syria, and the moment when the civilians become refugees. The photograph that follow then captures a small section of the Mediterranean where a lot of them disappear. I was heading to Lesbos, the island where refugees typically land. Just before I got there my friend Foad, a Kurdish fighter, messaged to say he is now in Turkey, will cross the sea and see me shortly. He never arrived. He disappeared in the sea. This project is a tribute to him.

Why include a snapshot of the Statue of Liberty on the harbour of Lesbos here?

When I asked refugees what they recall from Lesbos, they say this statue, because it reminds them of New York’s Statue of Liberty. There is a connection to past immigration, to history here.

The exhibition concludes with a series of fading blue renderings, made through the old cyanotype photographic printing process. Why did you choose for these images to be ephemeral?

I wanted to create pictures that will gradually fade. The blue monochrome becomes a double metaphor – the sea where so many lives are lost, where a lot of refugees disappear. But it is also the colour of Europe, and the refugees who make it will be part of the future of Europe.

This is a complex, expressive project and viewed together, these photographs and moving images form a compelling narrative. Your work is deeply considered, with authenticity central to this exhibition.

Yes, it took a long time to make these personal connections and form trust. It was important for me to give a different vision, not the one offered by photojournalism but by art. Art has a real place in society; as artists we have a public space and with this comes responsibility. Art cannot change society directly, but with art you can influence people’s perceptions.

What is your next project?

Working on the theme of climate – constructing different fights against climate change.

This interview was first published in Wallpaper*