The Art of Interconnection

Portrait of Tomás Saraceno outside the Serpentine gallery. Photography ©Dario J Laganà/Studio Tomás Saraceno

Tomás Saraceno is a fascinating artist whose work is devoted to exploring how we might better cohabit the Earth with nature and other species. Through his practice – particularly his intricate web sculptures – the celebrated multidisciplinary Berlin-based artist has spent over a decade observing spiders and their complex worlds. In doing so, he weaves new threads of connectivity within our own lives, noting, “it is exciting to see how spiders coexist and to then create these collective dialogues.”

Recent exhibitions have been a true tour de force of environmental art (if such a term can be applied to Saraceno who shuns labels) positioning him as both artist and instigator, and inviting us as viewers to actively question and rethink our relationship with the world and its other inhabitants.

At the entrance to Tomás Saraceno in Collaboration: Web[s] of Life at Serpentine South gallery in 2023, for example, we were asked to surrender our phones as our gadgets were safely slotted in what appears to be an old wooden shelving unit and exchanged with an oracle card, Arachnomancy Card, containing a personalised message (mine read: Planetary Drift). We were free, of course, to choose not to give away our phones. Yet it seemed a missed opportunity: to truly immerse in the lively and layered Tomás Saraceno world required this small sacrifice. And it paid off.

Tomás Saraceno in Collaboration: Web[s] of Life, at the Serpentine Galleries South. Photography ©Studio Tomás Saraceno

What a relief not to reach out for the iPhone at every photo opportunity (and there were many), to be fully present in the moment, and absorb the chapters that unfolded in each room and onto the surrounding Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park. As Saraceno’s first major exhibition in the UK, Web[s] of Life took on an awful lot — call it a web of actions — all of which set out to observe how different life forms, technologies and energy systems are connected in the climate emergency. Art, for Saraceno, holds active agency.

Born in 1973 in Argentina and trained originally as an architect, Saraceno is a multidisciplinary artist in its truest sense of the word whose work is all about the interconnectedness across ecosystems. He has been working with spiders for over a decade, observing their ways through creating safe environments for these leggy creatures to weave their architectural delights. He says it’s about investigating ways of coexisting more positively with nature and weaving new threads of connectivity within our lives.

Visiting his Berlin studio a little while ago, I met with other artists of all ages, with scientists and historians, a philosopher and a specialist in animal vibrational communication. There were spiders of all shapes and sizes, some in contained areas, some roaming free, weaving webs solo or collaboratively. Saraceno projects almost always involve collaborating with experts outside the art world. For Web[s] of Life at the Serpentine, he had worked with the Salinas Grandes and Laguna de Guayatayoc communities of Argentina to conceive a film installation showcasing the effect of mining and manufacturing, primarily lithium extraction driven by the high demand for batteries for phones and electric cars, on indigenous communities, with representatives invited to give a talk on the subject at the opening.

Spider/Web Pavilion 7: Oracle Readings, Venice Biennale (2019). Photography ©Studio Tomás Saraceno

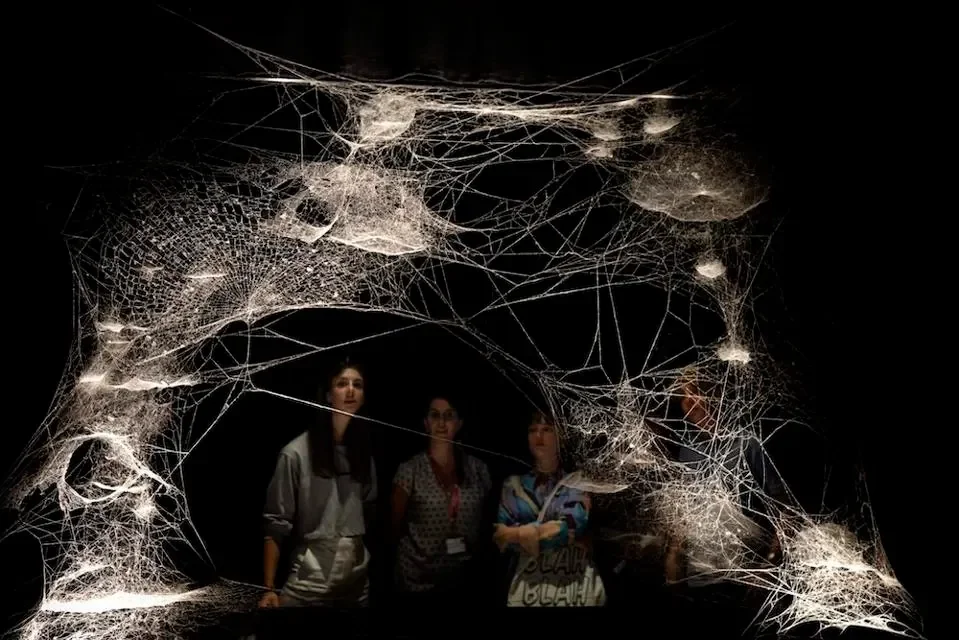

There were other collaborators too: outdoor sculptures made with animal specialists to attract wildlife, an educational playroom co-created with children, and best of all, in a darkened room, his famed web sculptures — created by spider artists and designed to shift our perception of who is the artist and who holds the voice. Saraceno wants us to question as he puts it: “Who is living at the Serpentine? How long have they lived on this earth? Who owns this planet?” Through this exhibition and others, he urges us to consider different knowledge forms, and to learn from them.

As a tangible commitment, the exhibition tracked its own energy consumption. For its duration, the Serpentine had to rely purely on solar power from specially installed panels on the gallery rooftop, air conditioning was turned off despite the summer heat, and certain gallery spaces remained dark if the sun didn’t shine. The show dared to be alive, sleeping and awakening to the rhythm of nature.

Saraceno’s hopes were for this to trigger a response in how visitors view their own personal life choices. And in a final act of performance (and bravery), the gallery had opened its doors fully exposed to the park, teasing nature to enter, asking all — visitors, park joggers and walkers and their pets, Londoners and tourists, sparrows and squirrels, foxes, bees and butterflies — to participate.

Tomás Saraceno in Collaboration: Web[s] of Life, Serpentine gallery (2023). Photography ©Nargess Banks

At ask Saraceno if he is using art to help make sense of the world. “Art is a tool to open dialogues; it offers the possibility to re-articulate and rethink,” he says. “I’m not too concerned with the category itself, as sometimes I feel we are victims of this, of the scientists telling us this, the artists telling us that, but with no one being able to make a radical change in the way we should shift how we live. This is why we need to form alliances. We need these connections, which are incredibly beautiful: art, science, and indigenous communities vibrating together. We can learn from the spiders and their webs; how they coexist and are so respectful to one another. And we need to recognise that we are many on this planet that can help one another for a mode of living that is much more sustainable.”

Through his work, Saraceno is urging us to rethink how we see ourselves as species, take a deeply critical look at our human-centric ways, and consider our interconnectivity to all other beings. And to learn from communities who have lived in harmony with nature for thousands of years. His work is a call to action. It tasks each of us to confront the reality of our fragile environment, see the interconnected webs that have led to where we are now, and see our efforts and actions within this ecosystem. It also offers hope. So much hope for a better future. And it represents what art should and could be: inclusive, collaborative and a collective of ideas and solutions.

This article was originally published in Forbes