Beyond the Line

Sean Scully, What Makes Us Too (2017). Photography ©Sean Scully

Two artists, separated by geography and time, embark on a lively conversation on abstraction as a medium for exploring the complexities of space, colour and perception, and inevitably history and politics. Beyond the Line, at Stefan Gierowski Foundation in Warsaw, Poland, unites the paintings and drawings of artists Stefan Gierowski and Sean Scully for what the curator Joachim Pissarro describes as “serendipitous conversations”. These are indeed staged exchanges, happening across time and place. Together, these paintings are layered and open-ended, grounded in the physical world while celebrating the vast possibilities of the imagination.

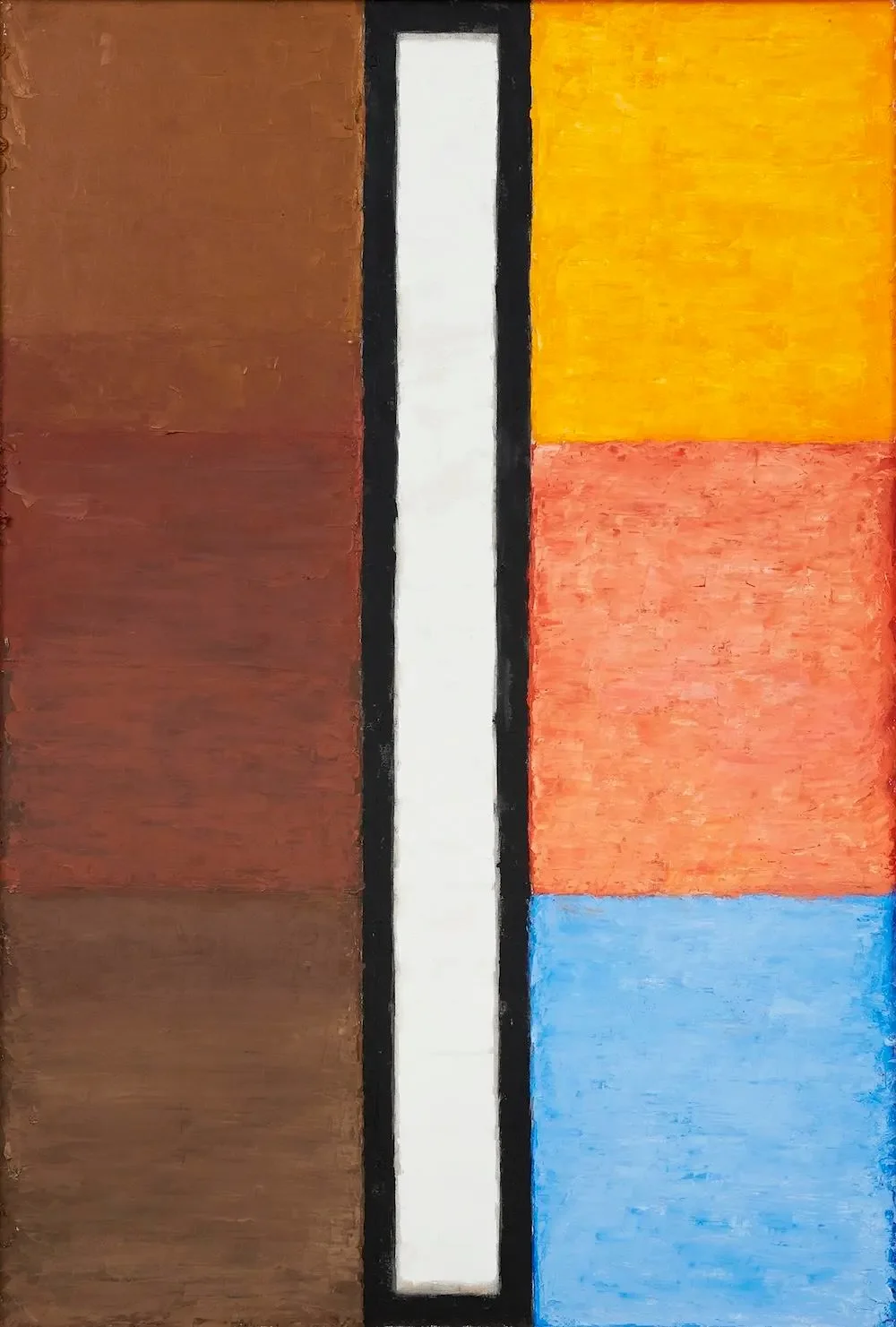

Gierowski, who passed away in 2022, is a critical figure in Polish modernism. His fascination was with light, optics and the metaphysical, his layered geometric forms made with almost scientific precision. Gierowski’s artworks seem like architectural compositions that task the viewer to engage with color as form and energy.

Meanwhile, born in Ireland in 1945, as an abstract painter and printmaker Scully works with bold stripes and vibrant blocks of colour, often with themes that explore identity and perception. Be it working in New York, where he made his big mark in the 1970s and 80s, or London where he lives today, Scully has cultivated a distinctive style, his richly textured artworks express the potential of intuition.

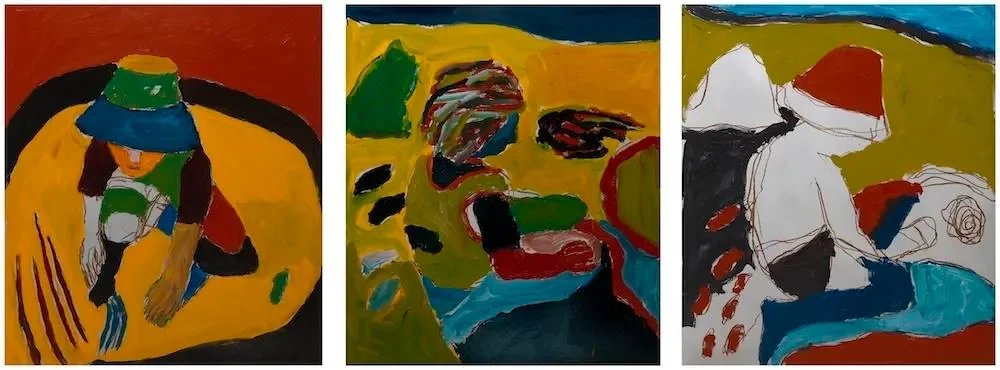

Sean Scully, Eleuthera Triptych (2018). Photography ©Sean Scully

Both artists share a profound dedication to abstraction, even if Gierowski’s compositions are meticulously crafted, and Scully’s exuding a sense of freedom and spontaneity, spirited and alive with visceral energy. Set against the minimalist white walls of the Stefan Gierowski Foundation gallery, Scully’s monumental pieces are raw, expressive compositions with overlapping bands of color that command the viewer’s attention. Gierowski’s work demands less of our energy but lingers on in the mind.

“What struck me so much from the start is that both Gierowski and Scully, even though they hadn’t met one another, use the same term in different ways: the term ‘resistance’,” says Pissarro — a word that informed his curatorial direction for Beyond the Line to be more episodes of conversations between the two artists rather than a chronological show of works. One room, for instance, features unlikely figurative works by the two, Gierowski in his early career, Scully in his later artworks — the former’s early works read as studies for the latter’s. Elsewhere, we encounter similar conversations across borders and time.

“In Polish history the word ‘resistance’ is a major force — whether we talk about the Warsaw Resistance against the Nazi occupation or the USSR,” Pissarro continues. “History has not been kind to this country. History hasn’t been kind to Ireland either, a country for too long under British rule. Both have extremely painful memories of having to fight against different systems and different powers. It’s been about resistance.”

Stefan Gierowski, Beyond the Line. Photography ©Adam Gut/Stefan Gierowski Foundation

As a curator and scholar, Pissarro’s work often tunes in on the intersections of art, culture, and history. His own family story — his great grandfather was the grandfather of impressionism, Camille Pissarro — is one of war and displacement. Here he also sees the weight of history and political context pivotal to both Gierowski and Scully’s creations.

My trip to Warsaw coincided with the opening of the Polish capital’s first Museum of Modern Art — a landmark project by the American architect Thomas Phifer that speaks less about the building and more about the country’s future-facing vision. Spending time in Warsaw is a sobering reminder of the power of history, of collective memories.

“I do believe this concept of resistance formed these characters and made them who they are,” Pissarro tells me. “I’ve learnt through conversations with Gierowski’s son and granddaughter, Hubert and Natalia who run the Stefan Gierowski Foundation, that he was a tough person.”

He continues, “As a teenager, Gierowski joined the Resistance during World War II, and he was nearly taken to the concentration camp by the Nazis during the German occupation. He lived a long time (he passed away at 97) and got to see Poland through its various histories. His family recall how he would always bring the conversation to the news, to politics.”

Stefan Gierowski, Painting CM (2012). Photography ©Adam Gut/Stefan Gierowski Foundation

Later that day when I spoke with Hubert, he recounted colorful stories of his grandmother housing the Warsaw Resistance in their grand residence, the occupying Nazi forces oblivions to this, thanks to the bourgeois grandeur of the building.

“Like I said, history has not been kind to Ireland either,” says Pissarro. “Scully also had a tough upbringing, in his case as a poor child with a mother who had to sing in pubs to make ends meet. Scully is a survivor though — a tough guy. He is therefore not an easy guy and tells you what he thinks,” Pissarro says with a smile. “It’s meant he never gave into trends and movements,” with the exhibition celebrating this so-called otherness that defines both artists.

Meanwhile, the title Beyond the Line is a nod to Scully’s linescape — a wordplay on landscape and a concept he coined to describe his abstract works to suggest a line can be more than a line. He has spoken of his paintings as an invitation to what he calls a “poetic space.”

Speaking of his main abstract work on show in Warsaw, Scully tells of me, “they never achieve resolution or conclusion, which is something very important in my work. The great poet Yeats spoke of the ‘divided soul’ in his poetry. This concept of double soul I also see in the work of Gierowski as a kind of restless anxiety—the anxiety of reaching a kind of perfection. I hate the idea of perfection and purity — I truly detest it, as in my view, it has a relation with fascism.”

I ask Pissarro how he sees these strong rebellious characters reveal themselves in their artworks. “There is a paradox to this” he replies, before exploring further. “With both artists there is a vibrancy that almost seems to contradict what I’m saying, which comes from when you’re in such a dark zone, as both artists have been. Then you also see in both artists a glimmer of hope, a spark of hope, manifested through this joyful exuberant colour scale. The two seemingly enjoy themselves. Scully gets a lot of joy from painting and I assume so did Gierowski.”

Sean Scully, Block (1995). Photography ©Sean Scully

Painting, Hubert recalls, was his father’s life. Towards the end of his life, although he could no longer see or paint, he would go to his studio to “feel the smell,” he says.

In a 1945 interview with the French writer Simone Téry for Les Lettres Françaises, Pablo Picasso described the artist as a “political being, constantly alive to heart-rending, fiery, or happy events to which he responds in every way.”

Pissarro believes the artworks on display at Stefan Gierowski Foundation reflect the moments in which the two artists created. “At the same time — maybe the paradox or contradiction—their work enables them to escape the moment in which they exist. I would say it’s a dialectic situation. This is the beauty of these works. We share this joy.”

Beyond the Line: From Finite to Infinite, From Physics to Metaphysics, Fundacja Stefana Gierowskiego 14 September to November 24, 2024.

This article was first published in Forbes